Exactly Why We Do What We Do (Part 2)

In Part 1, it was proposed that all training decisions benefit from being contextualized within The Cycle of Supercompensation.

Said another way, if we shepherd our athletic processes through this field of thought, we will become exceedingly good at: 1) designing our schedules, 2) executing our sessions, 3) recovering from stressors, and 4) navigating mental and emotional athletic challenges alongside the joys and hardships of life outside of training.

But enough precursory talk. Let’s get into what this looks like on a practical level.

Step 1: Understanding The Cycle

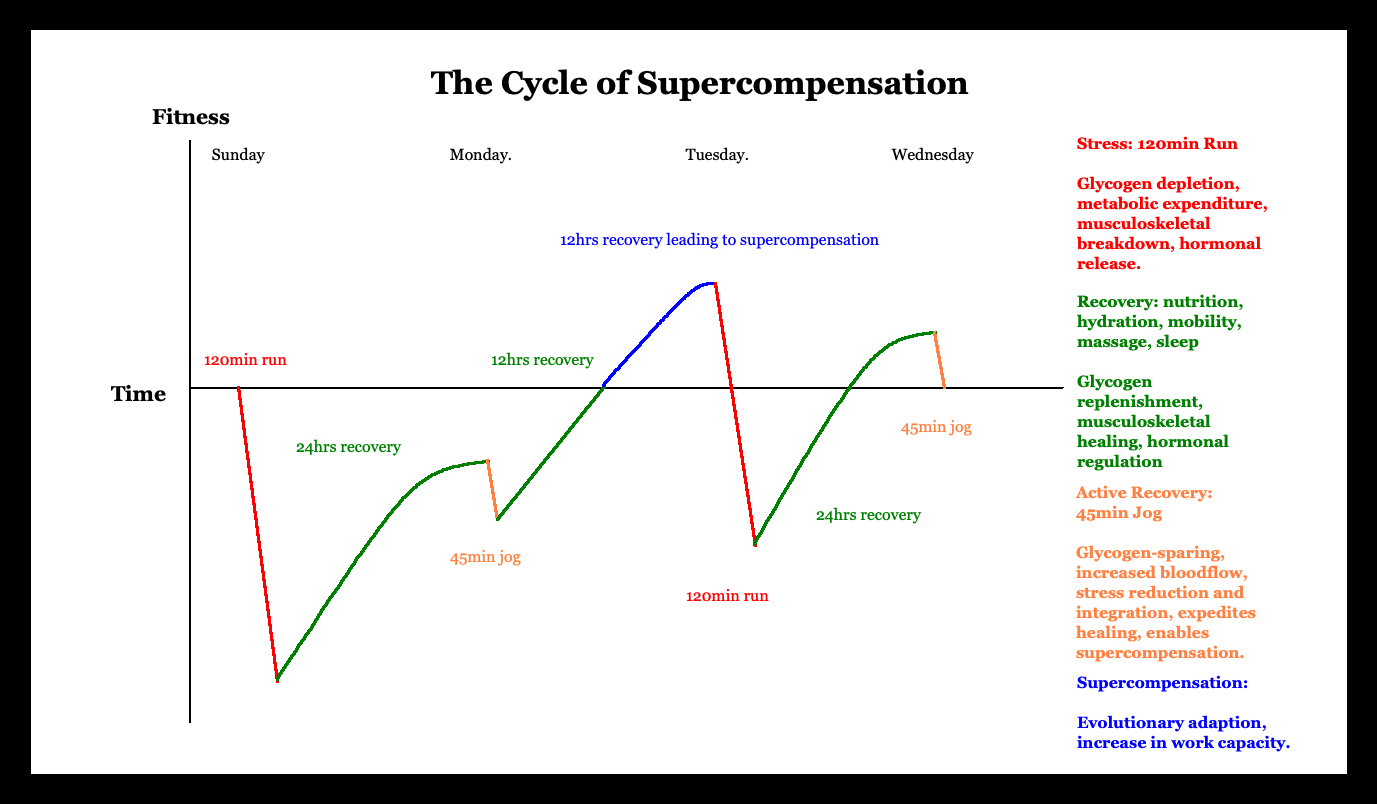

The x-axis is Time. For our purposes, let us focus on a 72-hour period; Sunday, Monday, Tuesday. Wednesday is included simply to illustrate how the cycle starts to look when repeated.

The y-axis is Fitness. This hypothetical athlete is an experienced runner performing a 120min run and a 45min jog on alternating days. By no means is this an optimal training regime. Rather, it is a high-contrast example used to illustrate the mechanisms of a cycle of supercompensation.

The red line is the strategic Stress: the 120min run. Make note of how the athlete’s fitness is not developed but broken down by the stress of the long run.

The green line is the Recovery. Nutrition, hydration, massage, a warm bath, compression, elevation, mobility work, spending time with others, fun activities, laughter, therapy, intimacy, sleep.

The orange line is Active Recovery. Performed at a low intensity, the primary source of fuel for this recovery session is endogenous fat stores. A 45min jog facilitates faster recovery of the prior day’s stress while remaining “glycogen-sparing”. This means that a well-executed Active Recovery session does not produce a novel stress, i.e., an additional recovery cost, but rather, it accelerates the assimilation of historic fatigue into current fitness.

The green-to-blue line illustrates how subsequent Recovery from an Active Recovery day leads to positive Supercompensation. In this example, after 12 hours of recovery from a 45min jog, this athlete has returned to their original fitness-level. But the body does not stop there! The strategic Stress of the 120min run, followed by 24 hours of impactful Recovery, followed by a 45min Active Recovery jog, followed by 24 additional hours of Recovery launches the athlete’s fitness to a new height. This miraculous enhancement is the holy grail of training: Supercompensation.

From this athlete’s new level of fitness, their capacity for similar work and their capacity to recover from that work is slightly advanced. Zooming out, if this athlete were to continue to honor each of the essential ingredients that produce this positive supercompensation cycle, their fitness will continue to increase, begin to plateau, and eventually level off; their physiology having fully adapted to the load.

But how do we use this stuff to generate constant clarity and progress in our training?

Step 2: Using The Cycle To Answer Almost Anything

Here is where I try to write myself out of a job.

Example 1: Bill T. Ninetofiver

Bill, 46, works Monday-Friday, 9am-5pm, and he is training for a Boston Marathon Qualifier in 6 months. Work is stressful, especially on Mondays. Nevertheless, he makes time to get the miles in during the week and his family supports longer outings on the weekends. 60% of his weekly volume comes from Saturday and Sunday and 40% comes from shorter runs during the work week. Bill describes himself as “injury-prone”, having battled tendonitis and plantar fasciitis in previous marathon builds.

Bill T. Ninetofiver (Before)

Bill is wondering how he can get more out of his training and increase volume without getting injured.

How can Bill use the Supercompensation model to reach a useful answer?

Scheduling. Firstly, Bill uses the model to recognize how he has a lot of stress clumped together on consecutive days. He sees how he would soak in more of his training if he were to “polarize” his days; he would absorb more of his long run if he were to follow it up with an active recovery day instead of a second long run. Secondly, he accepts that Mondays are his most stressful day of the week and decides that it would make for a good rest day. This is a really useful piece of the puzzle for him because now he starts to see how a schedule is almost self-evident. If he takes Monday off, then Tuesday is an opportunity to put forth a generous effort. Consequently, Bill sees Wednesday as an active recovery day, Thursday as a bigger day, and Friday as an active recovery day. Deciding to run long on Saturday or Sunday is all but answered for him. Running long on Saturday let’s Bill recover with a jog on Sunday. Taking Mondays off to set a good tone for the workweek, Bill has created a supportive infrastructure for not only his athletic progress but for his career as well. He has used the model of Supercompensation to formulate an effective training blueprint.

Bill T. Ninetofiver (After)

But can it actually fit his lifestyle?

Execution. Bill looks at his blueprint and identifies the big challenges of making this happen. Tuesday and Thursday mornings—things need to change. Compared to his old ways of training, he sees how he would do well to redistribute his volume more evenly across the week—let Tuesdays and Thursdays take up more of the charge so that weekends are recoverable efforts. He will either need to wake up earlier, run in the evenings, or even double during the final phases of his training. Slightly earlier bed times on Mondays and Wednesdays would support this change. The upside to this is that, in contrast, Bill’s Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays will feel more open. These days need not be additional sources of stress, but rather, pure support pieces for his bigger days. Gentle running for just long enough to accelerate recovery and he can end it there, shower, and get to work. Perhaps he will not be able to adhere to this blueprint every week, but getting as close as he can within the practicalities of work and family life will still prove superior to his past training architecture.

Recovery. Bill recognizes from the graph that it is not the runs in-and-of-themselves that make him a better marathoner, but his capacity to produce and then recover from stress that will get him a BQ. At work, when he remembers, Bill stands from his desk and walks around the office to limber up and increase blood flow. At home, he dusts off his foam roller, yoga mat and massage gun and sets them within reach for evening recovery practices. He starts to see these little efforts as equivalent to miles logged. As a means of honoring a more polarized training schedule, he finds himself scheduling social gatherings and other energetically demanding events on his bigger days to chunk things together so that he can reserve the evenings of his recovery days to be quiet, regenerative times with his family; playing games, talking, watching a good show, reading a book.

Real Life. Sometimes, Bill cannot get his run in because he needs to take his kids to school. Sometimes Bill loses track of time in the morning and by the evening, he is so tired from work that he is not motivated to run. Sometimes, family comes first, work comes second, and the marathon comes last. Life happens. But despite this, continuing to contextualize his choices within the framework of the cycle of supercompensation, Bill can navigate these obstacles. He does not fret when he misses a run because he knows that he has the energy budget to do something big the next day. He finds that having this cypher is a useful way to make scheduling decisions outside of running and that the order and clarity that such provides reduces his overall stress load. It is not always perfect, but his process feels underpinned by the notion of supercompensation and he continues to see progress in his training.

Example 2: Wanda T. Gravelnurse

Wanda is a committed gravel racer and a nurse in the ICU on a block schedule. She works 12-hour shifts Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday.

On her days off, she loves nothing more than to ride her bike. Wanting to take advantage of the time she has to train, Wanda fills her days off with epic 3-4hr rides at variable intensities. On work days, she either takes off or begrudgingly gets on the indoor trainer at night for short spinout rides.

Wanda T. Gravelnurse (Before)

Wanda had some great performances in her first couple racing seasons but has since found it hard to put in the saddle-time she feels she needs to be confident and dangerous on a starting line.

With her non-negotiable schedule and a few recent lackluster performances, Wanda is curious how the model of supercompensation can return her to form.

How can Wanda use the Supercompensation model to improve her training?

Wanda takes a look at her old training logs. She can hardly believe the amount of volume she used to put up. She cross-references these training progressions with the model of supercompensation. An inconvenient truth emerges. Perhaps she performed well at gravel races in the beginning, not because of her training, but in spite of her training. She recognizes that her 3-4hr rides at variable intensities probably produced massive recovery costs; that healing from these loads within a 48-hour period would be nigh impossible for an individual with a gentle work schedule, let alone her acutely stressful career.

For many highly motivated athletes and business professionals, the most difficult shift to make in training is not summoning the grit to do more, but rather, summoning the requisite tact needed to let their recovery capacity dictate usable training volume.

Wanda decides to make a change. Less training stress, more recovery.

Scheduling. Monday’s 4hr ride at variable intensities becomes a 2hr ride; low-intensity, high cadence. Tuesday, Wanda performs a 45min spin on the trainer before work to insure she does not skip the session that evening. Wednesday’s 3hr ride becomes a 2hr spin with short accelerations; just enough to stay in touch with her top-speed. On Thursday Wanda gets in another brief recovery spin before work. Friday is Wanda’s preferred long ride day and she caps her duration at 3hrs. Saturday is reserved solely for work. And Sunday is 90mins with “sweet spot” intervals included.

Wanda T. Gravelnurse (After)

Execution. Wanda pares back both her durations and effort levels in service of balancing stress and recovery. However, this does not mean her training is all long, slow, easy riding. There is still ample volume at lower intensities to contribute substantially to the ongoing development of her aerobic engine. There is also more finely structured quality-work peppered in to the training week. The challenge with executing these shifts is getting used to riding at lower intensities for long amounts of time while simultaneously bringing powerful intensity if and when the plan does call for it. Wanda notices that if she respects the monotony of her low-intensity rides, when it does comes time for structured sweet spot intervals, or maximal power outputs, or tactical skills training, she is hungry for it and can drop the hammer when it counts—all while coming away with a manageable recovery cost.

Recovery. Gradually coloring in the missing components of her recovery infrastructure, Wanda slowly begins to see her labors bearing fruit. Each time she coasts into her driveway after a long ride, Wanda considers how to make a decisive shift from depletion to replenishment; a protein shake, water and electrolytes, mobility work, foam rolling, getting the bike clean and another kit ready for the next ride, taking a shower, making dinner with a friend, taking her mind off of all things riding and work—having a good laugh. A significant reduction in total stress load coupled with myriad recovery strategies in the hours before and after big rides, Wanda starts to feel the stoke-level returning. On her work days, Wanda rolls with what comes; managing stressful situations as best she can within the given circumstances. Some days are unbearable, others are manageable. COVID has increased the stress level of her work by many orders of magnitude. Bringing greater attention to the cycle of supercompensation has not only made it exceedingly clear how deep a hole Wanda had dug in her training, but how much she had dissociated from the challenges of her work.

Real Life. Wanda does not feel the change overnight. Weeks of doubt ensue. Is this change-up having any measurable impact? Sometimes, Wanda hits snooze rather than getting on the indoor trainer before work. Sometimes, a particularly traumatic shift results in her staying home instead of going for a ride or seeing friends. Other times, the motivation to make another protein shake, to clean another muddy cassette, to do another load of laundry—it is all too much. More immediate forms of comfort take precedent. Life happens. These are hard times. But on the whole, Wanda feels more grounded and accountable to her athletic processes. The overarching context of supercompensation provides nuanced assurance, stability and flexibility in the face of uncertainty. Her supercompensation cycles move from a negative trajectory to a positive one. Her stoke-level returns. Power readings rise. Wanda finds herself clicking “Register” on race websites again. And eventually, she finds herself back on a starting line, feeling wiser—and more dangerous—than ever before.

———

The 3rd and final part of Why We Do Exactly What We Do.will be out in the next couple weeks, highlighting other athlete examples, outlier cases, and exceptions to the rule!

Thanks for reading!

Nathan Toben